Every high school chemistry textbook teaches that when you add salt, such as NaCl, to water, it results in an ionic solution that contains sodium cations, Na+, and chloride anions, Cl–. These charged, mobile species enable processes such as electrochemical water splitting and de-icing by salting roads in the winter.

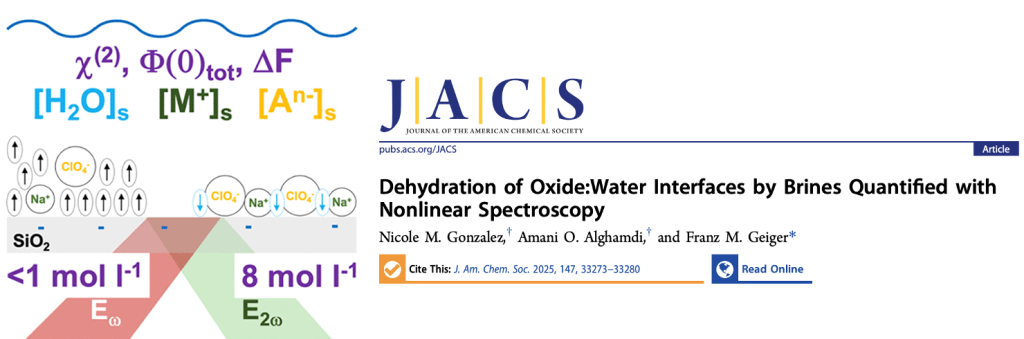

Now, our new research shows that this situation is different at interfaces. In a study we published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, we directly measure the coverage of water and ions on silica:water interface under extreme salt concentrations, conditions where most experimental tools lack sensitivity. What we find overturns assumptions: instead of ions endlessly crowding the surface as more salt is added, the system reaches a surprising balance (half a monolayer of ions and half a monolayer of water molecules), the latter having flipped their orientation from “protons to the surface” to “oxygens to the surface” at the highest concentration. This work shows that when you keep adding salt to water, at some point you don’t add the charged ions like Na+ and Cl– anymore but rather ion pairs such as [Na+…Cl–], where the net charge is zero.

At these high concentrations, the interface is thought to undergo a Kirkwood transition, signaling the phenomenon of an order-to-disorder transition in the state of matter that is much more subtle and nimbler than what happens when water freezes or boils. The findings suggest that electrostatic screening, commonly described by 100-year old Debye-Hückel theory, is subject to ion-ion correlations, clustering, and the emergence of new particle-particle interaction length scales that require new theories for liquids and interfaces.

Our results provide the first surface-specific experimental benchmarks of interfacial ion and water coverages as well as interfacial energies at extreme salt concentrations, benchmarks to which theory must conform. This structural change is likely to alter properties such as the dielectric constant and confirms long-standing predictions that concentrated electrolytes can drive water into a mediator for a catalysis-favoring state.

The discovery opens new frontiers for understanding catalysis, fluid transport in porous media, and advanced electrolytes, areas central to clean energy, environmental chemistry, and biology.

Read our article : https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/jacs.5c11999

Leave a comment